-

1. Introduction

On the eve of her retirement as the Editor-in-Chief of the Journal Law and Religion, Marie Failinger offered a reflection, in which she used the metaphor of a garden to describe scholarly writing in law and religion in America (Failinger 2014, p. 9). The stalwart plantings in the garden are the mainline traditional law and religion studies, which asked the question on the relationship between the state and religious organization (Ibid., p. 11). The historical and political scholarship is ‘heirloom tomatoes,’ which retells the actual history that shapes our imagination about religious freedom (Ibid., p. 11). The perennial vegetables in the garden are the scholarships that focus on the role of religion in the highly pluralistic, contentious society in which we live (Ibid., p. 13). Then, there are grafted plants, which engage with studies on law and religion on their own terms, pointing to missing insights from their religious traditions and experiences (Ibid., p. 14).

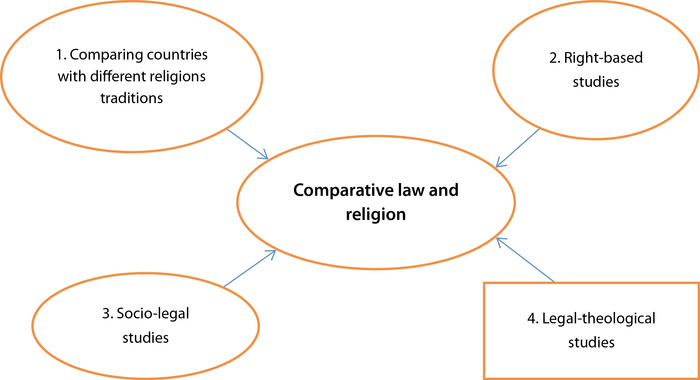

Unlike domestic studies on law and religion, comparative studies on law and religion, however, are still growing and have not produced a big garden. While comparative law and religion studies have flourished in the past decade, they have not given birth to many specialized law journals, textbooks, or web-based academic blogs. This article is a modest attempt to broaden and expand the garden of comparative law and religion with new genres, themes, and ideologies. This article will be divided into two parts. The first part focuses on the task of modifying the map of comparative law and religion. The current map of comparative law and religion shows that there are three types of approaches: (i) comparing countries with different religious traditions; (ii) rights-based comparison; and (iii) socio-legal comparative law and religion. In modifying the map, this article set out an agenda for a new cluster for comparative law and religion, which compares law and religion from a theological perspective. I would like to call this new cluster ‘Legal-theological Comparative Law and Religion’. With a keen focus on theology, the new cluster will widen the scope of comparative law and religion, which will include comparative inquiry coupled with theological insight.

This article argues that the essence of comparative law and religion is not only the act of comparing the legal system of one country to that of another, but also has a broader mission to compare the relationship between religion and law in the respective countries. The basis for comparison in law and religion is often our understanding of the legal system in two or more countries. But in many jurisdictions, religion drives and influences the legal system, and so, we must look beyond the law. Comparative theorists in law and religion should understand at least the basic religious doctrines and know how to systematize those doctrines. In other words, comparative theorists of law and religion should integrate theological knowledge in their studies, so they will be able to excavate the underlying structures of religion, and understand better how theological ideas influence the law. The bottom line is that to get a complete understanding of the nexus between law and religion; we need to include in the study of comparative law a question of how and to what extent theological ideas influence law within a legal system.

In what follows, in the second part of the article, I propose a three-dimensional (3D) analysis of the new legal-theological cluster, looking at integration, collaboration, innovation and beyond,1xThe three dimensional approach is inspired by the argument of integration, collaboration and innovation in the field of biblical ethics. See Chan 2015, pp. 112-128. through which a more comprehensive engagement with comparative law and religion can be suggested. -

2. Comparative Law and Religion: An Overview

2.1 Mapping the Field of Comparative Law and Religion

It is hard to dispute the significance of religious revival in late-twentieth-century and early-twenty-first-century politics. In the last four decades, the world has witnessed the return of religion to world politics, from the rise of political Islam in Muslim majority states to the increasing role of Islam in European politics through the wave of immigration. The world has also witnessed the rise of the Christian right in the United States, the growing influence of Catholicism in Africa, and the spread of Pentecostalism in Latin America. With the return of religion in the public square, there has been growing intellectual interest in the scholarship of comparative law and religion.2xThe scholarly works on comparative study of law and religion became more apparent in the early 1990s, and the initial works arose within international human rights studies. Arguably the most influential publication in this period is two volumes, Religious Human Rights, which resulted from a conference on the subject organized by Emory University. See Witte & van der Vyver 1996.

With the rapid growth of comparative law and religion scholarship, a more detailed mapping of the field becomes necessary. The challenge is how we can draw a nice map of comparative law and religion studies? The task is quite complicated because there are many variables in the equation. The complexity arises from the difficulty of postulating what kind of law or jurisdiction one would like to compare, and which religion or what aspect of religion that one would like to consider in the study. In this article, I would like to provide a modest proposal to draw a map of comparative law and religion. After the revival of comparative constitutional law in the 1990s (Fontana 2011), comparative law and religion seem to have emerged in three different main groups: comparing countries with different religious traditions, rights-based comparison, and socio-legal comparative law and religion.2.1.1 Comparing Countries with Different Religious Traditions

The first group of scholarship focuses on the comparison between countries with different religious traditions, which link the studies either on broader legal topics, such as constitutionalism in general, or particular legal topics such as freedom of religion. One of this group’s seminal works is Ran Hirschl’s Constitutional Theocracy (Hirschl 2010). Hirschl’s Constitutional Theocracy provides a sophisticated analysis of the relationship between religions, constitutions, and courts from countries with different religious traditions. One end of this spectrum is occupied by Muslim majority states, such as Egypt, Kuwait, Pakistan, Malaysia, and Turkey. At the other end of the continuum, Hirschl brings together countries with different religious traditions, such as India (Hindu majority) and Israel (the Jewish state). Hirschl also extends his comparison to secular countries with a rich Judeo-Christian heritage in Europe, Latin America, Canada (and South Africa). Hirschl tries to do quite a lot in his book; he covers multiple topics, ranging from co-optation of alternative religious discourses to political control of judicial appointments, with the agenda of promoting judges who have secularist leanings. Moreover, he also extends the narrative to real cases, such as women’s rights and religious symbols (hijab and crucifix).

Within this group, one can trace some scholarships that tackle a different topic, such as the comparison of blasphemy and apostasy law in countries with different religious traditions (Cata Backer 2015). With the spread of the hijab controversy in Europe, some scholars began to make a comparison between the approach of some European countries and the United States in handling the wearing of hijab in public (Tourkochoriti 2012). In the midst of the culture of war, a comparison between state neutrality in the United States and Europe was a good topic to explore (Haupt 2012). The topic of comparative criminal law and religion (see, for instance, Hascall 2011), or comparative family law and religion also contributes to studies in the first group (Akila Choudhury 2012; Tagari 2012).2.1.2 Rights-Based Comparative Law and Religion

If the first group engages with a comparison between two or more countries with different religious traditions, the second group typically undertakes more of a rights-based approach. As I attested earlier, the mapping is a complex task, and one will immediately encounter a challenge to make a distinction between the first and second groups. Take, for example, the scholarships of a leading Israel comparative theorist, Gila Stopler. Stopler devoted most of her studies to comparing the religious tradition in her home country, Israel, to countries with different religious traditions. Logically, her scholarships will fall under the first group. But some of her academic contributions also focus on women’s rights, which make some her works not fit well within the first group.

In her recent article, Stopler provided a comparative analysis of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the Hobby Lobby case and the European Court of Human Rights decision in SAS v. France (Stopler 2016). Hobby Lobby involved the question of whether free exercise of religion can exempt employers from providing contraceptive benefits that were mandated by U.S. federal law.3xSee Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2751 (2014). SAS v. France, however, dealt with a different issue of the banning of the full covering of the face in France. If Stopler chooses to render her analysis within the first cluster, she would investigate how both the French laïcité and the American religious freedom balance religious interest with the larger interest of society.4xFor an excellent comparative analysis on the French laïcité and the American religious freedom, please see Gunn 2004. Nevertheless, Stopler’s core investigation was on how these two cases affect women’s right to control over their bodies, and she concluded that in both cases, disempowered groups whose rights are restricted are women and the right that is restricted is their autonomy over their body. In other words, her analysis is about the comparison of women’s rights, instead of a comparison of the way the two countries organize religion.

In sum, the second group has an explicit commitment to take rights as its point of comparison, but it is a bit more amorphous in comparing religious traditions. In contrast, the first group, which focuses on the comparison between countries with different religious traditions, has a more straightforward approach in comparing religious traditions.2.1.3 Socio-Legal Comparative Law and Religion

The third group consists of the scholarship by comparative theorists who use the socio-legal approach in their research. Two elements characterize socio-legal comparative law and religion. First, it replaces the formal understanding of ‘law,’ with a socio-legal one, and often, the term ‘legal culture’ is used. David Nelken argues that in its most general sense, ‘legal culture’ should be seen as a way to describe ‘stable patterns of legally oriented social behavior and attitudes’ (Nelken 2012, p. 310). Nelken argues that if we want to work with the idea of legal culture, we have to specify what units we are referring to (Ibid., p. 315). Here, the concept of legal culture becomes more diverse because the cultural unit is susceptible to a different definition, depending on the level and purpose of the analysis. We all participate in various cultural units: the culture of our states, of our cities, of our families, and our religion. So, for a socio-legal theorist such as Nelken, religion will be taken into account as a single cultural unit within the larger legal culture.

The second element of the socio-legal approach is that it focuses on the issue of how law and society are related in a causal way. Mattias Siems provides a good explanation of the relationship between law and culture, in which he offered several categories that can describe the relationship between law, culture, and religion (Siems 2014, Chapter 6). The first category is a religious influence on the positive law; take, for example, Christian values that may still play a role in many legal systems such as in the area of family law and consumer credit (Ibid., p. 125). Second, religion may affect the law in a negative way; namely, there is no law in the particular area of interest (Ibid., p. 125). For instance, some Islamic countries do not adopt derivative transactions because they would be considered as gambling, which is prohibited in Islam. In the third category, religion is part of the law, in which there is no separation of law from religion (Ibid., p. 125). For example, the rules covering marriage, divorce, inheritance for Muslims in Indonesia is governed by Islamic law, instead of civil law (Ibid., p. 125). Siems provided three more categories,5xIn the fourth category, the issue is how the law impacts on religion, such as the way religious organization may be structured and financed. The fifth category involves the question of how religion influences the effect of the law; the case of Latin American countries indicates that due to strong Christian values, family ties can remain strong without a common family name. In the sixth category, there are cases where there is conflict between law and religion, which involves a question of how religious believers try to reconcile their duties as citizens and believers. See Siems 2014, pp. 126-127. but due to space constraints, I will keep the discussion for another day. The bottom line is that the causal relationship between law and religion are topics of socio-legal comparative law and religion.2.2 Modifying the Map

The map above is far from perfect, but at least, it can help us place existing scholarly contribution in comparative law and religion in three groups: comparing countries with different religious traditions, rights-based comparison, and socio-legal comparative law and religion. While not denying the importance of the scholarly contributions within the current map, I see the need to expand the map of comparative law and religion. Why do we need to expand the map?

First, the classic problem of comparative law is that a comparative theorist usually has more familiarity with his or her original jurisdiction. Therefore, often, he or she has some bias in comparing the original jurisdiction with different jurisdictions. Similarly, most of the scholars who work in the area of law and religion are legal scholars and not theologians. Thus, they tend to place a high emphasis on legal analysis and downplay theological aspects of the studies.

Take, for example, the growing comparative scholarship in the area of women’s rights, especially the right to abortion, which focuses primarily on the rights to abortion as their point of comparison while taking into account religion in their studies (Pfeffer Billauer 2017; Liviatan 2013; Siegel 2012, Albert 2005; Fleishman 2000). Specifically, if one wants to write about the right to abortion in Latin America, it is almost impossible not to link the studies to the role of the Catholic Church in the abortion debate (Goodwin & Whelan 2015; Oberman 2013; Johnson 2013; Kulcycki 2011; Shepard 2000). These scholarships, however, are not comparing the Catholic Church’s theology on abortion with other religious traditions, but rather, they are comparing rights to abortion, and religion is only in the background, and often, the religious argument also gets distorted in the debate. An apt example is a recent work of Barbara Preffer Billauer on abortion, in which she compares abortion regulation in five Catholic majority countries: Ireland, Poland, Italy, France, and Mexico (Billauer 2017). But Billauer only devotes one sentence to state the Catholic belief that human life begins at conception, without any reference to the document of the Catholic Church (Ibid., 308). Billauer does not seem bothered to go deeper looking into Catholic teaching on the sanctity of human life.

Second, methodologically speaking, comparative research on law and religion is not only about collecting data and information on religion or consulting religious groups. Comparative theorists in law and religion also need to understand at least the basic religious doctrines and know how to systematize and justify religious doctrines. It is not enough merely to offer a general description of religious teaching in comparative research on law and religion. Comparative law and religion research also should identify a theological insight that influences the law. Theology is a complex field, and so, one at least needs to have a basic understanding to examine those fundamental elements of theology, through which doctrine is to be applied, discovered, interpreted, and evaluated.

Third, comparative theorists on law and religion may also suffer from their limitations as non-religious individuals. In other words, the challenge for a comparative theorist of law and religion is how to remain objective as an outsider to certain religious traditions. While I do not deny the value of a researcher’s (outsider) objectivity, there are at least two concerns that arise from an outsider perspective. First, as an outsider, often, a researcher does not have a first-hand religious experience, and so, they might have less familiarity with the language, narratives, and ritual rhythms of the faith traditions in their attempt to frame and explain about the interweaving of law and religion.

Moreover, as an outsider, comparative law and religion theorists might be reluctant and even somewhat hostile toward the religious view. David Nelken, a leading scholar in the cluster of socio-legal comparative law and religion, makes it clear that the central premise of modernity is that no group has privileged access to moral truth (Nelken 2012, p. 48). Therefore, the role of law is to establish a secular and ‘neutral’ process for conflict resolution, rather than to endorse one set of cultural practices or religious beliefs over another. Here, Nelken echoed John Rawls, the best-known exponent of liberal theory, who introduced the notion of state neutrality (Rawls 1996, p. xxiii). Rawls’s state neutrality discourages any comprehensive religious views that do not conform to his reasonable comprehensive worldviews, such as Roman Catholic theology, which not only claims to be founded by God and have a supernatural origin and character, but also recognizes the moral and spiritual authority of the Church over political matters such as education and marriage (Kozinski 2013, p. 37). Religious views such as Roman Catholic theology must be excluded because it aims to impose its values upon others (Ibid., p. 8). In other words, the state then must not favour any religious doctrines and their conception of the good if it wants to preserve unity based on the private conception of the good of each citizen (Rawls 1996, p. 190). While this approach is what some would call objective, it does not fit with the language of religion, which includes the claim about truth. The fact of the matter is every religion—Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, Bahai, Sikhism, etc.—all of them have the claim of truth.

Having explained the limitations of the current map, I would like to add a fourth group of comparative law and religion studies, which compares law and religion from a theological perspective. I would like to call this group the ‘legal-theological comparative law and religion.’ The point of departure of this group is that one will investigate the nexus between law and religion from the theological perspective. The revised map could be drawn as seen in Figure 1. To distinguish the group, I have used ellipses and a rectangle respectively.Map of comparative law and religion studies

With this modified map, the study of comparative law and religion becomes somewhat expanded. In other words, this new cluster widens the academic terrain of comparative law and religion. With theology as the point of departure, one will be able to engage with a theological understanding of the law, instead of putting religion in the background of our comparative law analysis.

-

3. Legal-Theological: Three-Dimensional Approach of Comparative Law and Religion

The first question that will arise at the outset is: what is the legal-theological approach? I would like to answer this question by proposing a three-dimensional approach of comparative law and religion, looking at integration, collaboration, and innovation, which will enable comparative theorists to expand their scope of research.

First Dimension: Integration

Despite the growing interest in the comparative study of law and religion, the integration of law and theological studies is far from satisfactory: comparative theorists do not read much of what theologians write, while few scholars of theology have an interest in conversing with comparative legal scholars. Besides the lack of interest, the complexity and different professional aspects of training between the two disciplines have perpetuated significant obstacles to integration.

Nevertheless, a few scholars have tried to integrate comparative law and theological studies. Clark Lombardi’s book State Law as Islamic Law in Modern Egypt is one of the more successful attempts of integration between legal and theological studies (Lombardi 2006). The book grew out of Lombardi’s doctoral dissertation at the Religious Studies Department at Colombia University. Therefore, it is not surprising that Lombardi managed to integrate his legal training and his religious studies training. The book is divided into two broad themes. Primarily, the first section (Chapters 1-6) deals with the Islamic understanding of authority and the means of deriving Islamic legal principles when the authoritative sources (the Qur’an and a limited body of authenticated hadiths) are silent. The second section deals with historical legal analysis on Article 2 of the 1970 Egyptian Constitution, the jurisprudence of the Egyptian Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC) in Article 2 cases, and the reception by the public, religious scholars, and secular jurists of the SCC’s rulings. While Lombardi’s book is a single country study — that is, Egypt — it serves as a reliable reference for comparative law theorists who want to integrate comparative legal theory and theological inquiry.

Zachary Calo is another pioneer in integrating comparative law and theology. Calo postulates theological jurisprudence, which is quite different from a theory of law and religion (Calo 2013b, p. 1083). In Calo’s view, the issue of law and religion has centred on issues of concerning church–state relations and the place of religion within the liberal political order. With his theological jurisprudence, Calo is hoping to pull theology into deeper conversation with legal thought, in which ‘theology be culturally contextualized so as to offer a response to the particular jurisprudential challenges confronting late modern secular culture’ (Ibid., 1088).

Calo’s attempt to advance the integration of law and theology is evidence in his article Christianity, Islam, and Secular Law (Calo 2013a, p. 879). In this article, Calo explores the nexus between law and theological developments by considering the work of four thinkers from the Christian and Muslim traditions: Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im, Abdulaziz Sachedina, Rowan Williams, and Pope Benedict XVI. Calo argues that what unites AnNa’in, Sachedina, Williams, and Benedict is a common recognition that religion needs the secular and the secular needs religion. The application of this common conviction to law and the legal system will require constructing systems and norms that avoid both the negation of religion by secular law and the negation of secular law by the religious. Traditional comparative legal scholars might easily conclude that Calo’s study is mistakenly characterized as a comparative study, primarily because the comparative legal content is quite minimalist. Nonetheless, at its best, this type of scholarship contributes to the integrational dimension of underdeveloped legal-theological comparative law and religion.Second Dimension: Collaboration

Most of the comparative theorists are not theologians, and therefore, it would be a challenging task for these scholars to engage with the integration of comparative law and theology. To deal with this issue, I would like to propose a second dimension: a close collaboration between comparative theorists and theologians. The first step to bring collaboration is by linking law schools to schools of theology. There should be a collaborative effort that can help comparative theorists and students to study law and religion so that they could examine religion as a distinct way of understanding and perceiving meanings of the causal relationship between law and religion in political and social life.

The first collaborative effort can take place in the form of collaborative teaching. A comparative theorist might start team-teaching with a theologian on a course in a law school around comparative law and religion, in which comparative legal perspectives on selected topics are first presented, followed by theological reflections and analyses on the selected theme. A different approach to collaborative teaching can also take place in the form of an interdisciplinary seminar, in which a comparative theorist and a theologian present their own framework dialogically in the classroom discussion.

The second model of collaboration can take the form of a collaborative research project to bring together many experts from the two disciplines. Tom Ginsburg and Thomas Miles observe the phenomenon of the increase in the frequency of co-authorship in the legal scholarship (Ginsburg & Miles 2011, p. 1785). Ginsburg and Miles argue that legal scholarship in the past decade has undergone an unprecedented transformation, marked by the rapid growth of interdisciplinary approach, especially empirical work such as law and economics (Ibid., p. 1786). Ginsburg and Miles further argue that co-authorship within the law is driven by empirical and interdisciplinary work that is itself influenced by outside fields (Ibid., p. 1825). Ginsburg’s analysis can be a basis for a comparative legal theorist to imagine co-authorship with a theologian. A collaborative writing and research between a comparative theorist and a theologian will be an excellent project that can serve the purpose of opening up avenues and encourages further dialogue and interaction between the two disciplines.Third Dimension: Innovation

Mary Ann Glendon once called for an innovative approach in comparative law studies, in which there should be a fruitful collaboration and interaction among comparatists, public international lawyers, international business law specialists, and all who labour on behalf of human rights (Glendon 2014). Similarly, there should be an innovative approach in the field of comparative law and religion, in which comparative theorists should be able to mediate between their love of legal studies and intellectual pursuit of theological studies. At the minimum level, it requires the mingling of comparative legal studies and theological studies. Nevertheless, the bridging between comparative law and theological studies is by no means limited to integrating law and theology. Other inter -or multidisciplinary approaches should be proposed by comparative theorists of law and religion.

Kristine Kalanges’ Religious Liberty in Western and Islamic Law is possibly one of the most underrated works in comparative law and religion (Kalanges 2012). While Kalanges only focuses on one single issue of religious liberty, she brilliantly weaves together international law, comparative law, theology, and legal-religious history to illuminate and address the theoretical and practical dimensions of religious freedom in the West, primarily United States and Muslim majority states such as Iran, Turkey, Egypt, and Pakistan.

Kalanges advances her argument through a comparative analysis of human rights instruments from the Western and Muslim worlds, with attention to the legal-political processes by which religious and philosophical ideas have been institutionalized. To support her argument, she investigates the theological origins of religious liberty in the U.S. Constitution, not only to John Locke and John Madison’s thought on religious liberty, but also back to Martin Luther and John Calvin’s theological understanding of freedom of conscience. On the other side of the coin, she goes deeper to investigate the Islamic theological understanding of freedom of religion. In the context of international human rights law, Kalanges recognizes that the Catholic Church is one of the important players, and therefore, she reviews the Catholic Church theological view on religious freedom, especially in Dignitatis Humanae. -

4. Conclusion

Jurgen Habermas describes the current stage of relationship between secular modernity and religion as follows: ‘the philosophically enlightened self-understanding of modernity stands in a peculiar dialectical relationship to the theological self-understanding of the major world religions, which intrude into this modernity as the most awkward element from its past’ (Habermas 2010, pp. 15–23). In Habermas’s view, modern reason, which has turned its back on metaphysics, should understand its relation to theology, and similarly, theology should engage seriously with post-metaphysical thinking.

There is no doubt that comparative law and religion studies are the sons and daughters of modernity. Therefore, most comparative theorist would view ‘religion’ based on what Charles Taylor call the immanent frame (Taylor 2007, p. 15). The new conception of God, man, and the law makes up what Charles Taylor calls as the distinction between the ‘immanent frame’ and ‘transcendental frame.’ Within the immanent frame, autonomous persons as collective agents can create their state and church, and be governed by their own laws (Taylor 2007, p. 543). The immanent frame then gave rise to what Taylor calls the modern moral order, which rejects the previously higher moral principles based on the divine laws (Ibid., pp. 159-171).

Within the transcendent frame, Taylor argues that human actions are pretty much action-transcendent with God and divine law as the foundation (Taylor 2007, p. 94). Many legal systems, however, have a complex mixture of the transcendent and immanent frames.6xTake, for example, the U.S. Constitution; upon arriving in the United States, Alexis de Tocqueville had an impression that the nation has two constitutional foundations: one rooted in biblical religion and the other in secular philosophy. See Tessitore 2004. One of the key questions for comparative law theorists is, therefore, how far comparative scholars want to rely on the transcendent frame in their studies. Also, comparative theorists might also inquire whether comparative scholars seek to stay only within the immanent frame.

Following Habermas’s proposal, it is time for comparative theorists on law and religion to engage in theological studies. The legal-theological approach offers an alternative to established modes of comparative of law and religion, which solely rely on the transcendental framework analysis. The legal-theological approach is not an attempt to insert religious value on legal debates, but rather, an attempt to redeem legal logic of comparative law and religion by relocating law and religion within both the immanent and transcendental frames.

As the contestation between religion and liberal states across the globe continues, it will be a challenge for comparative legal theorists to conduct comparative studies on law and religion. With the ‘return’ of religion in political life across the globe, comparative scholars might become more reluctant toward transcendent, natural-law arguments. In other words, we will see the tendency of exclusion of the transcendent frame from intellectual discourse. This approach, however, will not bring any good to comparative legal studies; what is at risk with the alienation of the transcendent frame is that comparative law will continue to be seen as undertheorized and lacking a coherent methodology. Comparative law scholarships can be mistakenly characterized as comparative law and religion mainly because they involved religious issues. Nevertheless, legal academics who produce such scholarships is often unaware of (or ignorant of) the basic theological principles and its influence into a legal system elsewhere.

I hope that by proposing a 3D approach, those interested in comparative law and religion may be able to see the depth (integration), length (collaboration), and width (innovation) of the proposed legal-theological analysis to expand the garden of comparative law and religious studies. References Akila Choudhury, C. (2012) Between tradition and progress: a comparative perspective on polygamy in the United States and India. U. Colo. L. Rev., 83: 963.

Albert, R. (2005). Protest, proportionality, and the politics of privacy: mediating the tension between the right of access to abortion clinics and free religious expression in Canada and the United States. Loy. L.A. Int’l & Comp. L. Rev., 27: 1.

Billauer, B.P. (2017). Abortion, moral law, and the first amendment: The Conflict Between Fetal Rights & Freedom of Religion. Wm. & Mary J. of Women & L. 23: 271

Calo, Z.R. (2013a). Christianity, Islam, and secular law. Ohio N.U.L. Rev. 39: 879.

Calo, Z.R. (2013b). Faithful presence and theological jurisprudence: a response to James Davison Hunter. Pepp. L. Rev., 39: 1083.

Cata Backer, L. (2015). The crisis of secular liberalism and the constitutional state in comparative perspective: religion, rule of law, and democratic organization of religion privileging states. Cornell Int’l L.J., 48: 51.

Chan, L. (2015). Biblical Ethics: 3D. Theological Studies 76: 112-128.

Failinger, M.A. (2015). Twenty-five years of law and religion scholarship: some reflections. Touro L. Rev., 30: 9.

Fleishman, R. (2000). The battle against reproductive rights: the impact of the Catholic Church on abortion law in both international and domestic arenas. Emory Int’l L. Rev., 14: 277.

Fontana, D. (2011). The rise and fall of comparative constitutional law in the postwar era. Yale J. Int’l L., 36: 1.

Ginsburg, T., & Miles, T.J. (2011). Empiricism and the rising incidence of coauthorship in law. U. Ill. L. Rev., 2011: 1785.

Glendon, M.A. (2014). Comparative law in the age of globalization. Duq. L. Rev., 52: 1.

Goodwin, M., & Whelan, A.M. (2015). Reproduction and the rule of law in Latin America. Fordham L. Rev., 83: 2577.

Gunn, T.J. (2004). Religious freedom and laicite: a comparison of the United States and France. B.Y.U.L. Rev. 2004: 419.

Habermas, J. (2010). An awareness of what is missing. In J. Habermas, M. Reder, & S.J. Schmidt (Eds.), An awareness of what is missing: faith and reason in a post-secular age (pp. 15-23). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hascall, S.C. (2011) Restorative justice in Islam: should qisas be considered a form of restorative justice? Berkeley J. Mid. East & Islamic L., 4: 35.

Haupt, C.E. (2012). Religion-state relations in the United States and Germany: the quest for neutrality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hirschl, R. (2010). Constitutional theocracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Johnson, T. (2013). Guaranteed access to safe and legal abortions: the true revolution of Mexico City’s legal reforms regarding abortion. Colum. Human Rights L. Rev., 44: 437.

Kalanges, K. (2012). Religious liberty in western and Islamic law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kozinski, T.J. (2013). The political problem of religious pluralism and why philosophers can’t solve it (p. 37). United Kingdom: Lexington Books.

Kulcycki, A. (2011). Abortion in Latin America: changes in practice, growing conflict, and recent policy developments. Stud. Fam. Plan., 42: 199-200.

Liviatan, O. (2013). From abortion to Islam: the changing function of law in Europe’s cultural debates. Fordham Int’l L.J., 36: 93.

Lombardi, C.B. (2006). State law as Islamic law in modern Egypt: the incorporation of the Sharī a into Egyptian constitutional law. Leiden: Brill.

Nelken, D. (2012). Legal cultures. In D. Clark (Ed.), Comparative law and society (pp. 310-329). Cheltenham, U.K.; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Nelken, D. (2012). Using legal culture: purposes and problems. In Nelken, D. (Ed.), Using legal culture (pp. 1-51). London: Wildy, Simmonds & Hill.

Oberman, M. (2013). Cristina’s world: lessons from El Salvador’s ban on abortion. Stan. L. & Pol’y Rev, 24: 271.

Pfeffer Billauer, B. (2017). Abortion, moral law, and the first amendment: the conflict between fetal rights & freedom of religion. Wm. & Mary J. of Women & L. 23: 271.

Rawls, J. (1996). Political liberalism (p. xxiii). New York: Columbia University Press.

Rubin, E.L. (2015). Soul, self, and society: the new morality and the modern state. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Shepard, B. (2000). The ‘double discourse’ on sexual and reproductive rights in Latin America: the chasm between public policy and private actions. Health & Hum. Rts., 4: 110, 113.

Siegel, R. (2012). The constitutionalization of abortion. In M. Rosenfeld, & A. Sajo (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative constitutional law (pp. 1057-1078). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Siems, M. (2014). Comparative law (chapter 6). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stopler, G. (2016). Hobby lobby, S.A.S., and the resolution of religion-based conflicts in the liberal states. Int J Constitutional Law, 14(4): 941.

Tagari, H. (2012). Personal family law systems – a comparative and international human rights analysis. International Journal of Law in Context, 8(2): 231-252.

Taylor, Ch. (2007). A secular age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tessitore, A. (2004). Alexis de Tocqueville on the Incommensurability of America’s founding principles. In P. Augustine Lawler (Ed.), Democracy and its friendly critics: Tocqueville and political life today (pp. 59-76). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Tourkochoriti, I. (2012). The burka ban: divergent approaches to freedom of religion in France and In the U.S.A. Wm. & Mary Bill of Rts. J., 20: 791.

Witte, Jr. J., & van der Vyver, J.D. (1996). Religious human rights in global perspective. Vol. 1: Religious perspectives; vol. 2: Legal perspective. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

-

1 The three dimensional approach is inspired by the argument of integration, collaboration and innovation in the field of biblical ethics. See Chan 2015, pp. 112-128.

-

2 The scholarly works on comparative study of law and religion became more apparent in the early 1990s, and the initial works arose within international human rights studies. Arguably the most influential publication in this period is two volumes, Religious Human Rights, which resulted from a conference on the subject organized by Emory University. See Witte & van der Vyver 1996.

-

3 See Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2751 (2014).

-

4 For an excellent comparative analysis on the French laïcité and the American religious freedom, please see Gunn 2004.

-

5 In the fourth category, the issue is how the law impacts on religion, such as the way religious organization may be structured and financed. The fifth category involves the question of how religion influences the effect of the law; the case of Latin American countries indicates that due to strong Christian values, family ties can remain strong without a common family name. In the sixth category, there are cases where there is conflict between law and religion, which involves a question of how religious believers try to reconcile their duties as citizens and believers. See Siems 2014, pp. 126-127.

-

6 Take, for example, the U.S. Constitution; upon arriving in the United States, Alexis de Tocqueville had an impression that the nation has two constitutional foundations: one rooted in biblical religion and the other in secular philosophy. See Tessitore 2004.

Citeerwijze van dit artikel:

Stefanus Hendrianto, ‘Comparative Law and Religion: Three-Dimensional (3D) Approach. Special Issue - Comparative Law’, 2017, oktober-december, DOI: 10.5553/REM/.000028

Law and Method |

|

| Artikel | Comparative Law and Religion: Three-Dimensional (3D) Approach. Special Issue - Comparative Law |

| Authors | Stefanus Hendrianto |

| DOI | 10.5553/REM/.000028 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Stefanus Hendrianto, 'Comparative Law and Religion: Three-Dimensional (3D) Approach. Special Issue - Comparative Law', LaM October 2017, DOI: 10.5553/REM/.000028

|

The nexus between religion and law is an important subject of comparative law. This paper, however, finds that the majority of comparative theorists rely on the immanent frame; that legal legitimacy can and should be separated from any objective truth or moral norm. But the fact of the matter is many constitutional systems were founded based on a complicated mixture between the transcendent and immanent frame. Whereas in the immanent frame, human actions are considered self-constituting, in the transcendent frame, human actions were judged in light of their correspondence to higher, divine laws and purposes. |